Number of heat-related illness and deaths rises as Coachella Valley sees more frequent heat waves and hotter days

Under the blistering sun, on a 117 degree day, it can feel like your skin is burning as you toil without shade. It's why farmworkers in the East Coachella Valley wear long sleeves, drenched in sweat they can never seem to replenish fast enough.

"It start in the lips, don't speak good," said Vidal Mendoza Fonseca, a farmworker who lives in Coachella Valley, referring to the slurred speech that he and his fellow workers can get if they work too long under the sun.

Fonseca has worked in the East Valley farms, picking bell peppers as well as other vegetables and fruits for the past 20 years. Sweaty chills, confusion, and more, he said, are symptoms he has seen throughout the years, which can be signs of heat exhaustion or heat stroke, the most serious of heat-related illnesses.

"Some people almost die," said Fonseca. "I see my body -- my body is changed. Every day is more tired, my body. It's very difficult, work very hard."

The money is not great, Fonseca said, but the work is year-round, which makes the searing temperatures worth the risk.

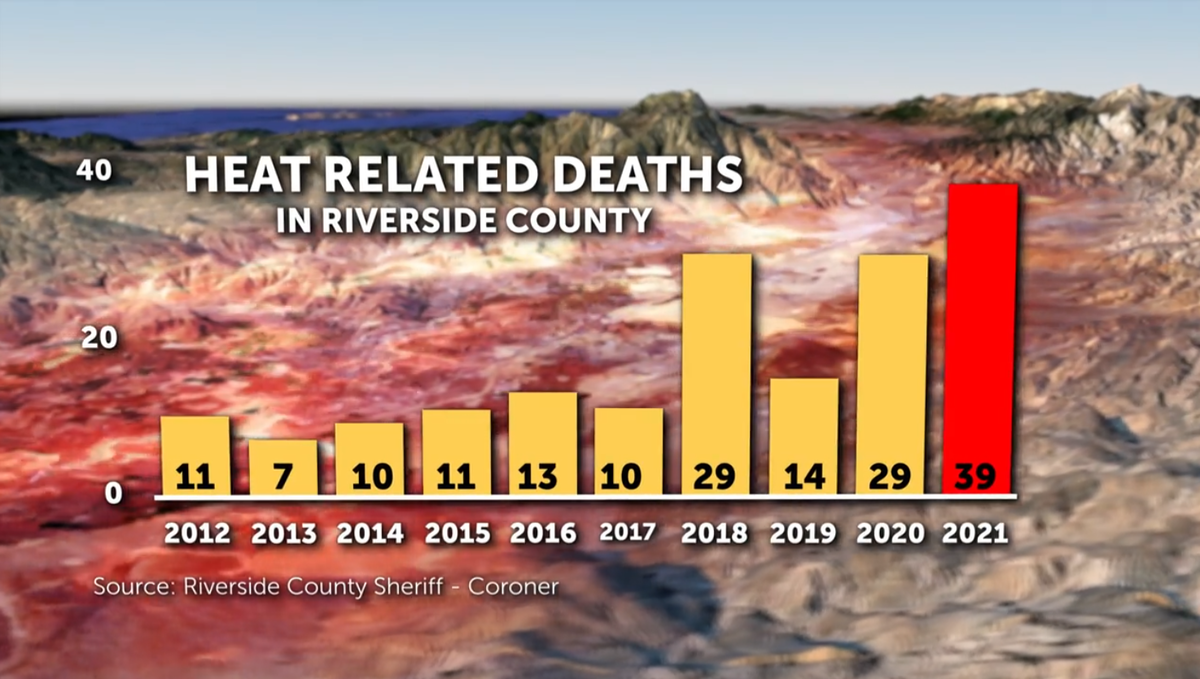

With climate change bringing more frequent and intense heat waves, heat-related mortality incidents in Riverside County reached a ten-year high in 2021 with 39 deaths, according to the Riverside County Sheriff's Coroner's Office.

It follows the soaring number of heat waves from that year. Our analysis of weather records from the National Weather Service shows more than half of July 2021 (16 days) broiled in temperatures 110 degrees or higher. June saw an all-time high of 123 degrees, which was nearly 14 degrees above the seasonal average.

And while the heat is dangerous for everyone, certain groups are at higher risk. Men are more likely to die of heat-related illness, according to the Riverside University Health System, with men seeing 78% of heat-related deaths from 2016 - 2021.

"Men tend to be more in the outdoor occupations that exposes them to high heat or the warehouse occupations where those facilities may not have air conditioning," said Wendy Hetherington, the chief epidemiologist of the Riverside County Department of Public Health.

Of all the races, the Black population is the most vulnerable.

"The Black community could experience a higher incidence of heat-related illness and death due to many factors such as access to health care, substandard housing, occupation, education choices," said Hetherington. "The root cause of lack of opportunity or access is structural racism in that historically, policies or systems were set up that unfairly advantaged the Black community."

110 degree days can bring fatal risks for poorer communities, who don't always have access to air conditioning, especially those in mobile homes. According to law enforcement officials, the elderly on a fixed income often feel forced to leave their air conditioners off because they can't afford high electricity bills.

"They're thrifty. They're trying to save on their electric bill. They won't turn up their air conditioner no matter how hot it gets, and they succumb to the heat," said Coroner Lieutenant Anthony Townsend of the Riverside county Sheriffs Coroner's Office.

California's growing heatwave problem is now a public health crisis, and heat-related deaths are often believed to be undercounted. That's because counties differ in how they count them.

"Riverside county is really particular about keeping an eye on heat-related deaths because more than two thirds of our county is the desert," said Townsend.

If heat played a role in the death, whether it's a primary cause or a contributing factor, Riverside County will count it. But, according to Townsend, that's above and beyond what is required by national standards. Other counties may only record the primary cause of death and not "other significant causes" which could include heat as a factor, meaning heat-related deaths could get left out of the count.

It's a California data problem that could soft-pedal how big our heat crisis really is.

During the recent 2022 Labor Day heat wave, a total of 183 heat-related emergency room visits was documented from the period of August 28 to September 10, according to officials from the Riverside County Department of Public Health. The average number of visits was 13 per day in that time frame. There were five days during this period in which a "trigger" went off, indicating that there were significant increases in the number of visits compared to baseline.

For the same time period last year, we only saw a total of 63 heat-related emergency room visits, with an average of 4.5 visits a day. There was no "trigger" during this time frame in 2021.

"Heat-related weather events are a top cause of human suffering and illness and death," said Hetherington. "Oftentimes people don't take high heat warnings seriously because it's something invisible."

It's why some health officials want governments to name heat waves like they do hurricanes. The Coachella Valley is getting hotter, with the desert trending upward in seeing more 110 degree or higher days. As of the air date of this story, Riverside County has seen 15 deaths, with 14 more pending from the Labor Day heat wave.

A large number of heat-related deaths here in Riverside County, are also drug deaths, with many under the influence when they die. But state lawmakers are responding to this growing public health crisis. California Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia has helped write a new law to create a first-in-the-nation extreme heat wave ranking and advance warning system.

"This will allow us to identify these specific hot spots in California and deploy resources with the intended goal being, one, to prevent heat-related illnesses and save lives," said Assemblymember Eduardo Gacia, who represents the 56th District.

The new law requires state agencies to develop a ranking system of heat waves and to make sure California residents are warned about it ahead of time. Garcia also emphasized that heat can be a silent killer and that these types of deaths are too often underreported. The goal of this new law is to save lives by helping people better prepare for deadly heat.