Daniel Ellsberg, Pentagon Papers leaker and anti-war activist, dies at 92

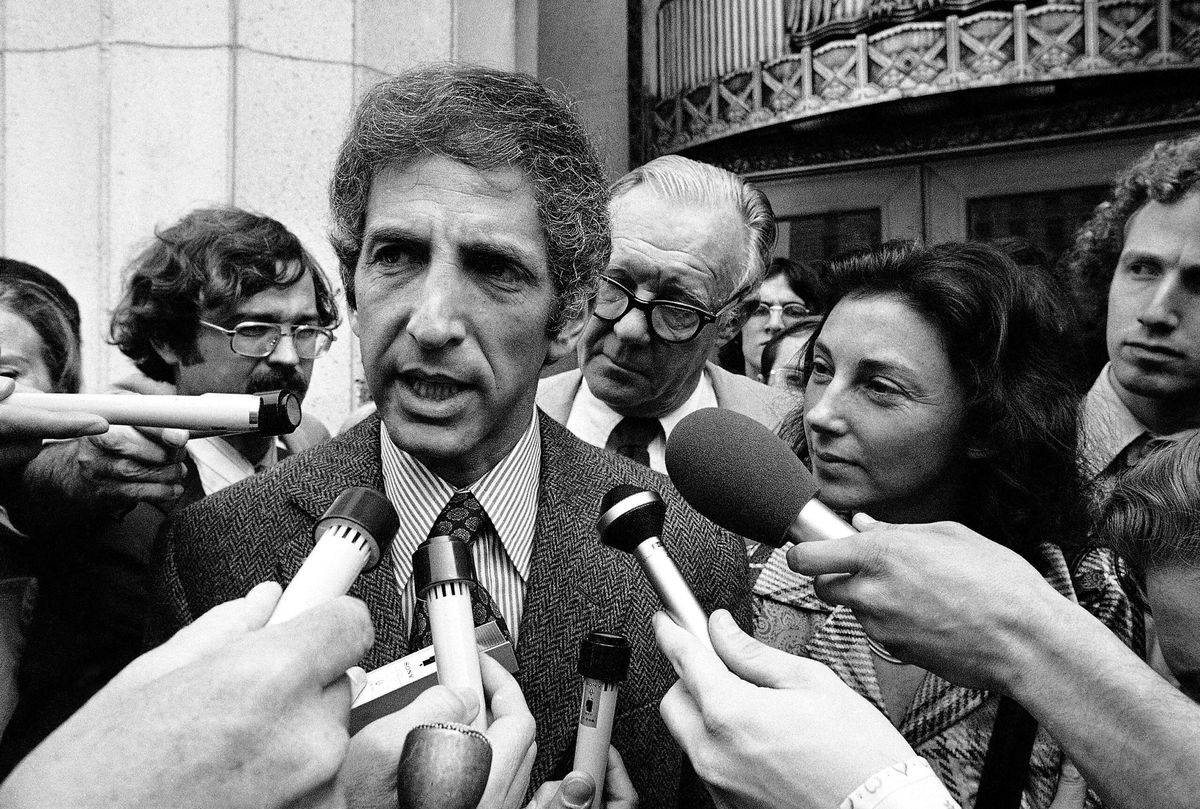

In this April 28

By Kaanita Iyer, CNN

Washington (CNN) — Daniel Ellsberg, a former military analyst and anti-war activist whose disclosure of the so-called Pentagon Papers revealed systemic US government deception about the Vietnam War, has died, his family announced in a statement. He was 92.

The cause was pancreatic cancer, his family said. Ellsberg announced his diagnosis in March, saying at the time that doctors had given him three to six months to live and that he had decided not to undergo chemotherapy.

He died on Friday at his home in Kensington, California, according to his family.

Considered “the patron saint of whistleblowers” for revealing to The New York Times in 1971 that the US knew the Vietnam war was “unwinnable,” Ellsberg spent his life focused on peace and transparency, later co-founding the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

“Daniel was a seeker of truth and a patriotic truth-teller, an antiwar activist, a beloved husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, a dear friend to many, and an inspiration to countless more,” his family said. “He will be dearly missed by all of us.”

In the late 1960s, Ellsberg was working as a defense analyst for the RAND Corporation when he became disillusioned with US involvement in Vietnam. As part of his work with RAND, Ellsberg had access to classified documents that demonstrated how the US government had systemically lied to the public about the war, and Ellsberg felt compelled to reveal the information.

He first approached several US senators in hopes that they could enter the papers into public record, but when that wasn’t successful, he leaked all 7,000 pages to The New York Times, which published them in 1971.

The documents revealed damning information against the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson administrations. While officials spoke optimistically about the war to the public and continued to send troops to Vietnam, they privately knew that the US was losing, with then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara advising President Lyndon B. Johnson as early as 1967 that American escalation would not win the war and, by some accounts, advocating for withdrawal.

Among other revelations, the report showed that President John F. Kennedy had approved the overthrowing of Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem – whom he and other administrations had previously supported – in 1963, according to The New York Times.

In an unprecedented move, the Nixon administration barred the Times from continuing to publish pages of the report after the first few stories. Ellsberg then leaked the document to The Washington Post, which was also sued by the government. The Supreme Court eventually ruled in favor of the two publications, concluding that the government had not made the case for censorship, and full publication of the Pentagon Papers resumed.

Ellsberg admitted to being the whistleblower and faced 115 years in prison after being charged as a spy under the Espionage Act. He was eventually freed after it was revealed that the Nixon administration wiretapped his conversations, resulting in a mistrial.

In a letter to his friends that he shared on social media in March, Ellsberg reflected on his decision to leak the Pentagon Papers.

“When I copied the Pentagon Papers in 1969, I had every reason to think I would be spending the rest of my life behind bars,” he wrote. “It was a fate I would gladly have accepted if it meant hastening the end of the Vietnam War, unlikely as that seemed (and was). Yet in the end, that action—in ways I could not have foreseen, due to Nixon’s illegal responses—did have an impact on shortening the war.”

The documents also had an impact in other ways. Along with further stoking the anti-war movement, the disclosures also contributed to a growing distrust of the federal government, a sentiment that would be further encouraged in the 1970s with the Watergate scandal and revelations of abuse by the national security state, such as those captured in the Church Committee report.

Sitting down with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour in late March, he expressed, among other things, joy at spending his final days with his family and eating whatever he wanted. “It’s been a wonderful party, it’s time to go home and go to bed,” he said at the time.

A hawk turned dove

Born on April 7, 1931, in Chicago, the Great Depression forced Ellsberg’s family to move to Detroit when he was 6 years old, according to the University of Massachusetts Amherst. A gifted student, he received scholarships to an elite preparatory school and, later, Harvard University.

Following a year of graduate studies in the United Kingdom, he returned to the US to enlist in the Marine Corps to support the US Cold War policy, according to Amherst. Following his service, Ellsberg returned to Harvard to work on his dissertation in games theory, which led him to join the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit think tank, in 1959 to work on nuclear war strategy.

In 1964, he joined the staff of the assistant secretary of defense for International Security Affairs, according to The New York Times, and worked directly on Vietnam policy.

He turned “from hawk to dove,” the Times wrote, in 1967 when he was in Vietnam as part of the State Department and came to the conclusion that “no change in tactics or reallocation of American resources could turn the tide of the war.”

Ellsberg returned from Vietnam and rejoined the RAND Corporation after contracting hepatitis, The New York Times reported, but until 1969, he continued to serve as a consultant to the government on the war, during which he had access to the classified documents.

In the over 50 years since the leak, he was a staunch critic of American intervention and nuclear war, conducting lectures, making media appearances and frequently protesting, which have led to arrests.

Ellsberg was among over 100 anti-war demonstrators arrested in front of the White House in 2010 and again in 2011 for rallying in support of Chelsea Manning, a whistleblower who leaked information about the Iraq War to WikiLeaks.

He also openly supported the leak of the Supreme Court draft opinion overturning Roe v. Wade last year.

“No organization really wants to show how the sausage is made or legislation is made, and they prefer to be the only voice on policy to the public,” Ellsberg told NPR. “The Supreme Court wants to get all the authority it can from hiding the nature of dissension; the details of arguments that people have made one way or the other.”

“It’s a very good thing that it got out. It was important to be out,” he added, calling such leaks “the lifeline of a republic.”

Ellsberg is survived by his wife, Patricia, his children Robert, Mary and Michael, five grandchildren and a great-granddaughter.

A public memorial, his family said, will be planned in the coming months.

This story has been updated with additional details.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

CNN’s Kevin Liptak and Cheri Mossburg contributed to this story.