FDA advisers vote that lecanemab shows benefit as an Alzheimer’s treatment

An advisory panel for the US Food and Drug Administration voted unanimously Friday that the Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab shows “clinical benefit” for the treatment of the disease

By Jacqueline Howard and Tami Luhby, CNN

(CNN) — An advisory panel for the US Food and Drug Administration voted unanimously Friday that the Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab shows “clinical benefit” for the treatment of the disease, paving the way for the medication to be considered for full FDA approval.

A decision from the FDA is expected by July 6.

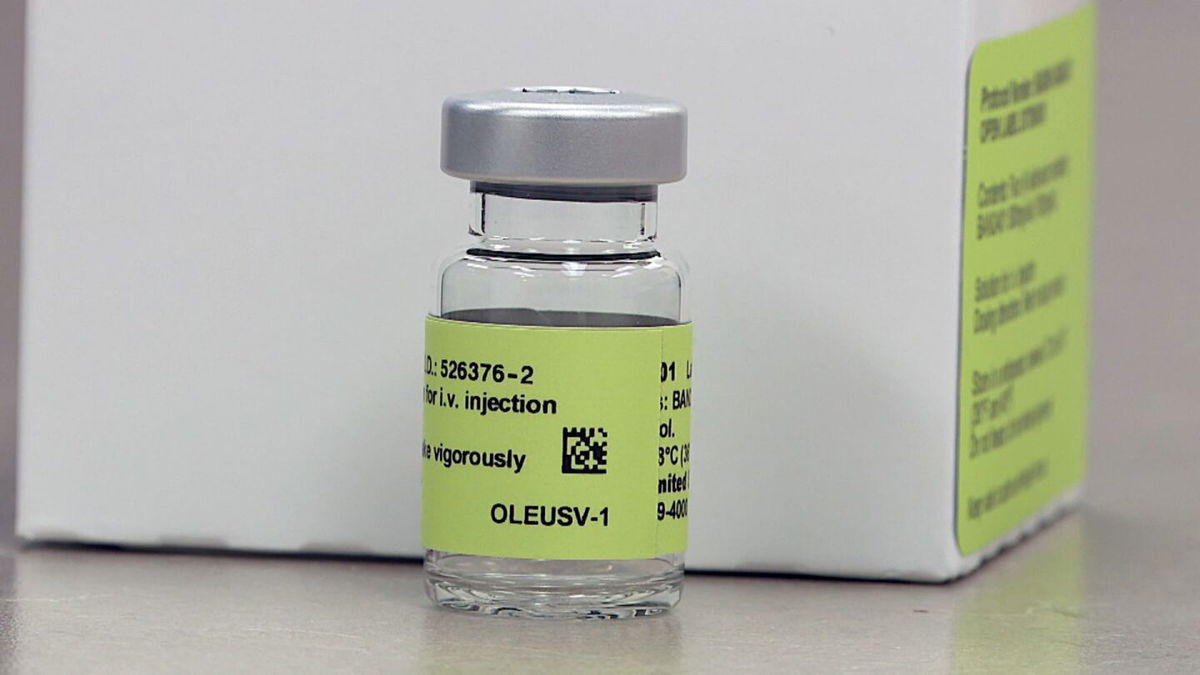

Lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody sold under the brand name Leqembi, is one of the first dementia drugs that appears to slow the progression of cognitive decline. The drug is not a cure but works by binding to amyloid beta, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

In January, the FDA granted accelerated approval of Leqembi for people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, even though there were some safety concerns due to the treatment’s association with certain serious adverse events, including brain swelling and bleeding.

The accelerated approval program allows for earlier approval of medications that treat serious conditions and “fill an unmet medical need” while researchers continue studying the drug to confirm, verify and describe its clinical benefit. If those additional studies show a benefit, the FDA can grant traditional full approval for the drug. But if the confirmatory studies do not show benefits, the drug could be taken off the market.

If lecanemab receives traditional FDA approval, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has said it will provide broader coverage – meaning Medicare patients could get greater access to the treatment. However, the coverage will come with some qualifications.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval CMS is prepared to ensure anyone with Medicare Part B who meets the criteria is covered,” CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure said in a statement this month.

Medicare will cover the approved drugs when a physician and clinical team participate in the collection of evidence about how these drugs work in the real world, also known as a registry, CMS said. Providers will be able to submit the evidence through a CMS-facilitated portal.

Patient groups and the pharmaceutical industry, however, have voiced concerns about the use of a registry, saying it will create a barrier to treatment.

“We are in full agreement with the FDA Advisory Committee that Leqembi provides clinical benefit and that this benefit outweighs the risks. Now all eyes turn to CMS,” Dr. Joanne Pike, president and CEO of the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement Friday. “Medicare is supposed to be a rock-solid guarantee for Americans, and it is time for CMS to step up and provide Medicare access on the day of an FDA traditional approval. Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease deserve access to FDA-approved therapies without barriers, just like people with cancer, heart disease and HIV/AIDS.”

The committee’s support for lecanemab serves as an “important milestone” on its pursuit for possible full FDA approval, experts say.

“The support vote for Lecanemab is an important milestone for every patient living with Alzheimer’s disease, every family with a loved one who is affected by Alzheimer’s disease, and indeed every person at-risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease in the future,” Dr. James Galvin, chief of cognitive neurology and director of the Comprehensive Center for Brain Health at UHealth – The University of Miami Health System, said in an email Friday. He was not involved in the FDA committee’s meeting.

“It has been nearly two decades since the last Alzheimer’s treatment received full FDA approval, and never before has a disease-modifying medication received full FDA approval,” he wrote. “This vote today almost assuredly will be followed by two momentous decisions – full FDA approval and agreement by CMS to cover treatment in some form. This is a critical issue to assure that all patients from all social and economic backgrounds have access to medication.”

What the science says about lecanemab

On Friday, the FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee met to discuss the results from a confirmatory Phase 3 study on lecanemab as drugmaker Eisai seeks full approval. At the end, members voted 6-0 in favor of the drug’s clinical benefit.

“We’ll consider whether any of the new data impacts our current understanding of the safety of lecanemab and the benefit-risk assessment,” Dr. Teresa Buracchio, acting director of the FDA’s Office of Neuroscience, said in Friday’s meeting.

In the study, 897 participants were given a placebo and 898 were given lecanemab, administered biweekly as an intravenous infusion. The study found that, 18 months later, lecanemab slowed disease progression by at least 26% in certain measurements, according to data that Eisai presented to the FDA advisory panel Friday.

“I thought the evidence for clinical benefit was very clear, very robust,” Dr. Merit Cudkowicz, chief of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and a member of the FDA advisory committee, said in the meeting. Many of the other members agreed.

The data also showed that 26% of participants given lecanemab had infusion-related reactions, compared with 7% of those given a placebo. Among lecanemab recipients, 17% had brain bleeding, compared with 9% in the placebo group, and 13% had brain swelling, compared with 2% given a placebo.

“These tended to occur early in treatment, supporting monitoring during the first six months of treatment,” Dr. Michael Irizarry, senior vice president and deputy chief clinical officer of Alzheimer’s disease and brain health at Eisai, told the FDA committee Friday.

The potential for side effects may affect the drug’s coverage, Michael Abrams, managing partner of the global health care consultancy firm Numerof & Associates, said in an email Friday. He was not involved in the FDA advisory committee’s vote but has been watching discussions around lecanemab closely.

“Despite the fact that Leqembi slowed cognitive decline in early Alzheimer’s patients by 27% in the trial, the treatment also carries serious risks of brain swelling and bleeding,” he said. “That could be reason for CMS to impose prerequisites on its use, limiting the number of patients who would qualify (at least initially) and mitigating the potential $5B cost to the program.”

In a previous study, about 6.9% of the trial participants given lecanemab dropped out due to adverse events, compared with 2.9% of those given a placebo. Overall, there were serious adverse events in 14% of the lecanemab group and 11.3% of the placebo group.

The most common adverse events in the lecanemab group were reactions to the intravenous infusions and abnormalities on their MRIs, such as brain swelling and bleeding, also known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA, which can become life-threatening. The drug’s prescribing information carries a warning about ARIA, the FDA says.

Some people who get ARIA may not have symptoms, but it can occasionally lead to hospitalization or lasting impairment. And the frequency of ARIA appeared to be higher in people who had a gene called APOE4, which can raise the risk of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. ARIA “were numerically less common” among APOE4 noncarriers.

The FDA advisory committee discussed concerns about lecanemab’s overall risks versus benefits for APOE4 carriers. “The ARIA rate was pretty striking,” said member Dr. Michael Gold, chief medical officer of Neumora Therapeutics.

More than 6.5 million people in the United States live with Alzheimer’s disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, and that number is expected to grow to 13.8 million by 2060.

Concerns about registry requirement

CMS angered Alzheimer’s advocacy organizations and drug makers last year when it restricted coverage of the controversial and costly medication Aduhelm to those enrolled in qualifying clinical trials, which limits the number of people who can receive the medication. Medicare had never before required enrollees to participate in a clinical trial for a drug already approved by the FDA that’s being used for its intended purpose.

The registry mandate for lecanemab has also raised concerns.

“We continue to believe that registry as a condition of coverage is an unnecessary barrier,” the Alzheimer’s Association said in a statement this month. “Registries are important tools to gather much needed real-world evidence to transform and improve patient care. But, registries should not be a requirement for coverage of a FDA-approved treatment.”

Not all patients will be able or will want to participate in a registry, PhRMA, a leading pharmaceutical industry group, said in a statement. Also, not all providers may participate in the registry, meaning seniors may have to find new doctors and travel to them.

“If Leqembi is given approval for wide-scale coverage, it could mean that those on Medicare would have the option of pursuing treatment, which would mean a significant spike in Medicare costs and a potentially arduous path for patients who would hope to qualify for treatment,” Abrams said.

Broad Medicare coverage of lecanemab and similar types of medications to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease would probably have a big impact on the program’s spending.

If 10% of the estimated 6.7 million older adults take lecanemab, at an annual list price of $26,500, it would boost spending by $17.8 billion, according to an analysis by KFF, formerly the Kaiser Family Foundation. That would exceed the total spending on the top 10 Part B drugs administered in doctors’ offices in 2021.

The increase in spending could lead to higher Medicare Part B premiums for all enrollees. Before Medicare even announced whether it would cover Aduhelm, it hiked premiums for 2022 by 14.5% in part to make sure it would have sufficient funds to pay for the medication, which was initially priced at $56,000 a year.

Medicare ended up reducing Part B premiums by about 3% for 2023. The decrease was driven in part by Medicare’s decision to limit its coverage of Aduhelm and by the manufacturer’s decision to cut the price.

Many Medicare enrollees may not be able to afford to take lecanemab even if it is covered. Those with traditional Medicare may have to pay more than $5,000 out of pocket annually, based on a 20% coinsurance requirement, KFF said. And those with Medicare Advantage plans are typically responsible for 20% coinsurance up to their plan’s out-of-pocket limit. (Last year, the average limit was nearly $5,000 for in-network services, weighted by plan enrollment.)

“While broader access to Leqembi could provide modest clinical benefits to older adults with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease, a significant increase in Medicare spending and premiums is a distinct possibility, and one that Medicare, patients, and taxpayers are likely to confront in the not-too-distant future,” KFF said in its report.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.