Understanding the significance of the US debt limit

Kevin Chen Images // Shutterstock

Understanding the significance of the US debt limit

The United States Capitol in Washington D.C.

The U.S. government has operated on a budget deficit in all but four years since 1970, making the accumulation of debt a crucial source of federal funding.

The Congress-imposed debt limit determines the maximum amount of debt obligations the federal government can hold at any given time. Raising this limit or suspending it for a specified period is necessary for the continued financing of various government programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, without an increase to the burden on taxpayers.

Once government debt hits the ceiling, the Treasury Department can no longer issue bonds, Treasury bills, or notes, and at that point must turn exclusively to tax revenues to settle its obligations. If the revenue falls short, the government risks defaulting on its debts. This could have devastating consequences for the economy, including interest rate spikes, a drastic drop in the value of the dollar, and disruptions to financial markets. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned a debt default would result in an “economic and financial catastrophe” and set off a global crisis.

While Congress routinely raises the debt ceiling every time it’s due, the issue has been used, many a time, for political point scoring. Historically, the minority in Congress has threatened to oppose raising the ceiling to wield more influence over fiscal policy. Similarly, this year’s impasse in Congress ended on June 1, just days before the default deadline, with the Senate passing bipartisan legislation to suspend the previous ceiling of $31.38 trillion until 2025.

Stacker compiled useful information on the recent fight over the debt limit with data from previous fights to provide context for this uniquely American phenomenon.

![]()

Mark Wilson // Getty Images

Congress came within just days of defaulting three times in the past 12 years

President Barack Obama speaking in the Brady Press Briefing Room at the White House after the U.S. Senate voted to end the government shutdown and raise the debt limit on October 16, 2013, in Washington D.C.

Reminiscent of this year’s scenario, a last-minute resolution in November 2015 saw Republican congressional leaders reach a deal with then-President Barack Obama. After 12 days of swift negotiations, a two-year budget accord was adopted, raising the limit by $1.7 trillion and averting a debt default by a single day.

A deadlock in October 2013 led to a 16-day government shutdown, with partisan dissent reaching a fever pitch before a bipartisan Senate agreement ended the impasse, once again just one day shy of the heralded default. In August 2011, the ambiguity surrounding a debt limit increase continued for so long that S&P downgraded the top-tier U.S. credit rating of AAA to AA+, in a first since 1941.

Anadolu Agency // Getty Images

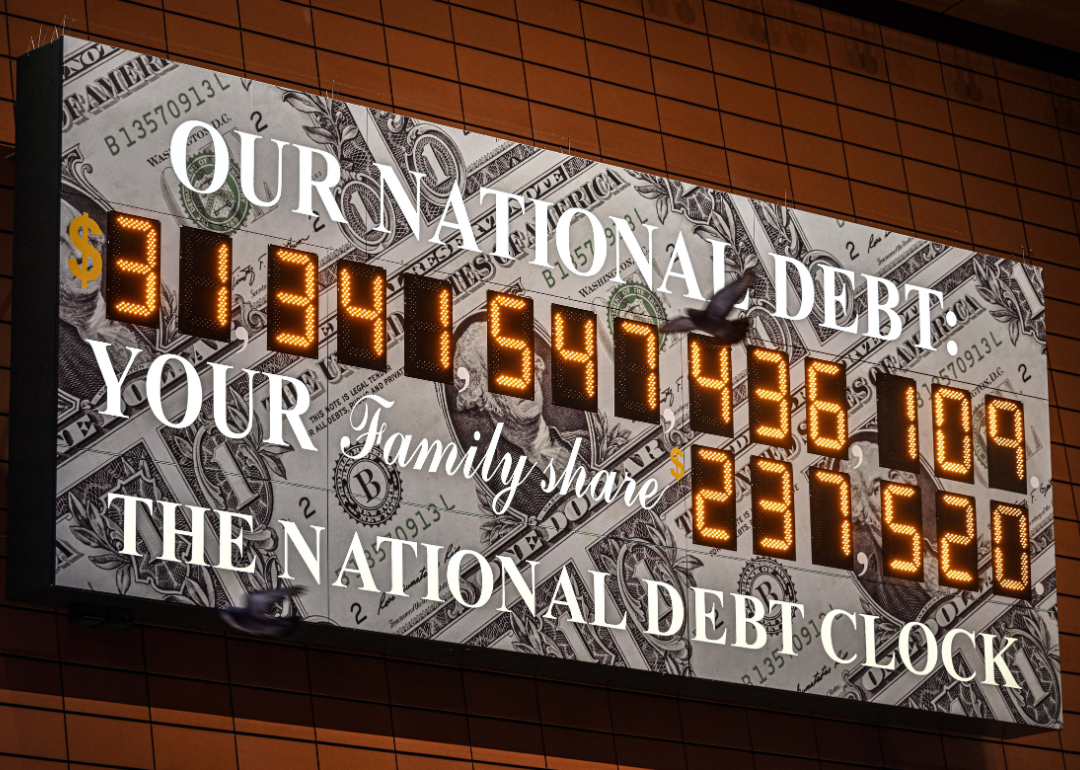

Repaying the national debt would cost more than $90,000 per person

A screen showing the national debt clock after the U.S. hit its debt limit and the Treasury started using extraordinary measures to avoid default on January 19, 2023.

Per capita, the national debt in the U.S. grew from about $12,800 in 1990 to just over $92,500 in 2022. Advocates for the full repayment of national debt often overlook the exorbitant burden such a measure would impose on individual taxpayers, as well as certain economic advantages of debt financing. Economists believe that high inflation, such as the current rates in the U.S., boosts nominal tax revenues and diminishes the real value of debt, thereby facilitating its repayment by the government. Historical evidence suggests that unexpected inflation has contributed to reducing the government’s debt burden, such as during the 1970s oil shock.

Santi Visalli // Getty Images

The last time the US paid off the national interest-bearing debt was in 1835. A major depression followed two years later.

The General Andrew Jackson Statue in Lafayette Square on December 23, 1996, in Washington D.C.

Mere decades after the Revolutionary War ended, the U.S. national debt ballooned to $120 million. President Andrew Jackson eliminated this debt entirely in 1835 for the first and only time in history. However, two years later, a land asset bubble burst, entailing bank runs and triggering a widespread economic crisis known as the Panic of 1837. This economic depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s, resulted in bank failures, high unemployment rates, and a substantial economic downturn. Even during the second Clinton administration, when the government operated at a budget surplus, debt was not entirely eliminated.

Kevin Dietsch // Getty Images

“Extraordinary measures” are budgeting tactics used to keep the government from defaulting on its debt while terms are established to increase the debt limit

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen testifies before the House Financial Services Committee at the Rayburn House Office Building on June 13, 2023 in Washington D.C.

In mid-January, the government reached the now-suspended debt ceiling of $31.38 trillion. However, with the help of “extraordinary measures,” the Treasury managed to stave off default until June. These measures included pausing certain types of investments in health plans for retired postal workers and government worker savings plans, as well as suspending the daily reinvestment of securities in possession of the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund. These tactics, while useful, can only delay a default by a few months. In January, Yellen cautioned that by June 5, these measures would be depleted.

Win McNamee // Getty Images

Actual spending cuts are relatively small but give some politicians “winning” talking points

U.S. President Joe Biden delivering a nationally televised address from the Oval Office of the White House on June 2, 2023, addressing the recent debt limit agreement that the U.S. Congress passed with broad bipartisan support.

The bipartisan debt limit agreement caps nonmilitary spending growth for fiscal 2024 at 1%, according to The New York Times. With a forecasted inflation rate of 2.6% for the following year, this effectively amounts to a spending cut.

Politico reported that the deal also withdraws $1.4 billion immediately from the IRS, with an additional $21 billion of the agency’s $80 billion—procured through the Inflation Reduction Act—set to be reallocated over the next two years. The agreement is projected to trim $55 billion in government spending overall—less than 1% of the $6.27 trillion spent last year. While the spending cuts negotiated fell short of what Republicans had originally aimed for, the deal provides potent talking points for the party’s opposition to an IRS funding boost.

Additional reporting by Sam Larson. Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Tim Bruns. Photo selection by Abigail Renaud.