Teachers come forward about safety issues at CVHS, school board refuses to respond

This school year has certainly been anything but certain.

KESQ has shown the public the alarming fights breaking out at Desert Hot Springs High School during the first semester. Now, we're looking into the fights at Coachella Valley High School.

There have been reports of broken noses, and kids being carried off by ambulance. In some of these fights, these students pummel each other, pulled away only when security guards drag them off, according to teachers we spoke with.

Some CVHS staff said they are burnt out just months in, saying they felt abandoned by administration.

"They don’t care. They don’t support you. There’s no consequences. I know for a fact, on campus right now, there were several teachers -- that a student will make a derogatory comment, racist comment or will be flat out be harassing and want to physically fight them and when it’s reported, the student is gone for two days and then they return," one teacher, who did not want reveal their identity, said.

"It’s so hard, it honestly is. These kids, it just breaks my heart. They come with so much baggage. And they do come from single households. And all they want is structure. That’s all they want,” another teacher, who also did not want to reveal their identity, added.

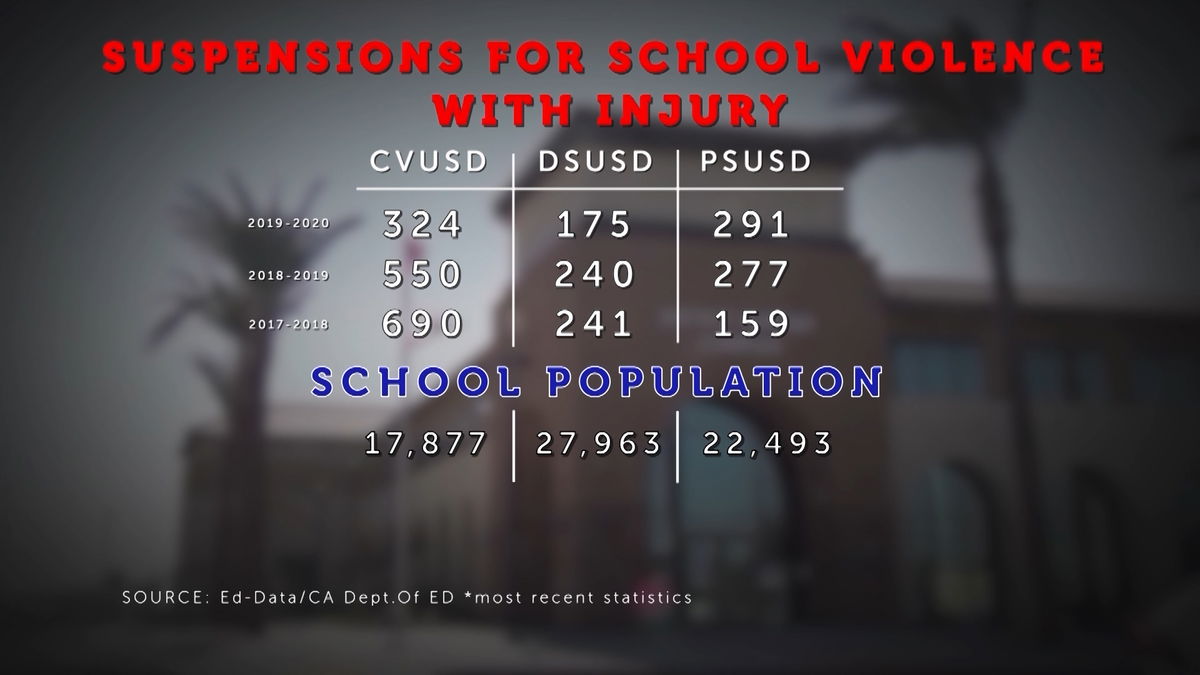

CVUSD has long had a higher incidence of school violence resulting in injury than the other two districts in the valley. It's the only valley district that doesn't have police officers assigned to its campuses, getting rid of them back in 2018.

A look at records over the past few years shows substantially more fights and violence resulting in injury here, even though CVUSD has the smallest school population.

"It’s not a safe environment for our students. If staff are being injured or hurt, students are being injured and hurt," said one of the teachers. "It’s a trickle-down effect. You can’t blame our students for being hesitant to go to school sometimes because of the fear of what’s going to happen on that day."

During the course of morning anchor Angela Chen's reporting, she found that the fear is very real, revealing that students who initially wanted to give an interview about how dangerous they felt the campus was backed out, saying they were scared they'd get jumped.

And while the Coachella Valley Teachers Association union had much to say about all this off-camera, they ultimately backed out as well and gave a simple "no comment" on the issues in this report.

KESQ also reached out to the CVUSD Board of Education. The president, Joey Acuna Jr, declined to speak with us on December 8, and instead, passed the interview to the new superintendent, Dr. Luis Valentino, who has only been in office for five-and-a-half months.

But after Valentino's office asked KESQ what we wanted to discuss -- with Chen answering promptly -- his office stopped responding entirely. News Channel 3 followed up several times and has given his office more than a month to answer -- and as of the airdate of this report -- only silence from his office.

Behavioral issues though aren't unique to CVHS. The pandemic has exacerbated mental health problems at schools across America.

"We've seen how COVID-19 has upended a lot of lives and contributed especially to students' greater academic and learning difficulties and mental health difficulties, like stress and anxiety and depression," said Julien Lafortune, a public education research fellow for the Public Policy Institute of California.

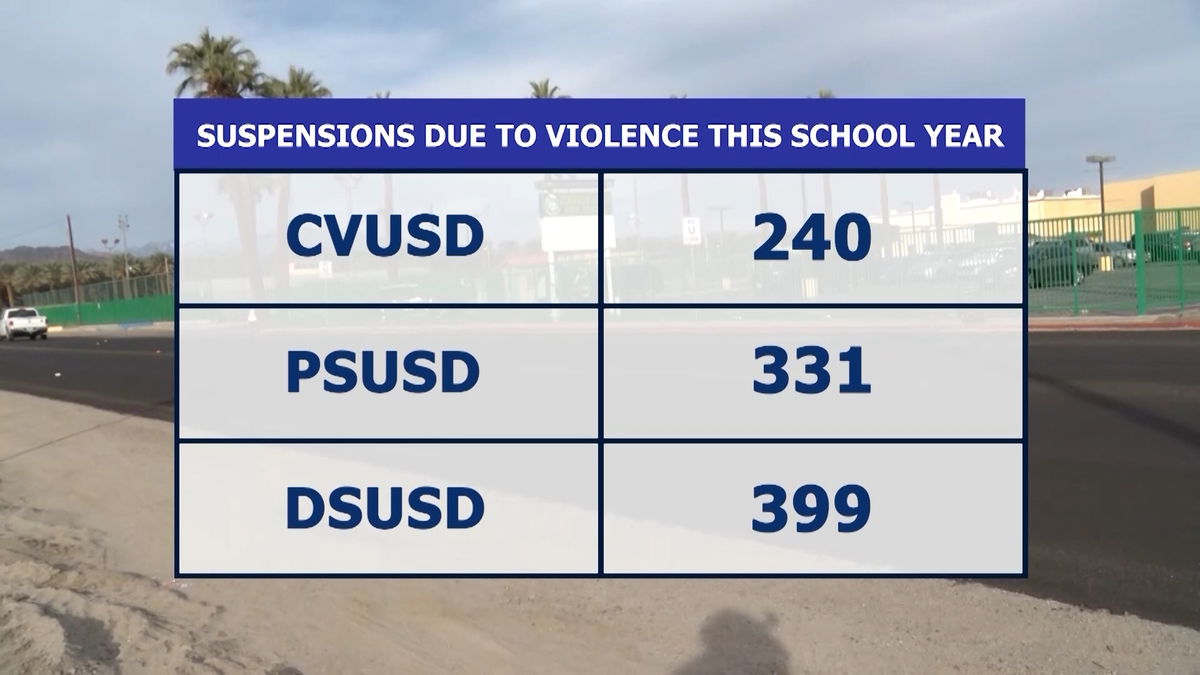

Still, for all the reported violence at CVHS during the first three months of this school year, the number of kids suspended so far this school year due to violence is the lowest at CVUSD, compared to Desert Sands and Palm Springs Unified.

Some teachers accuse CVUSD of trying to make itself look better on paper by keeping suspension rates down.

It could explain why school violence with injury is its highest suspension category -- compared to Desert Sands and Palm Springs, which both have fights without injury as their highest.

Either CVUSD has very few fights without injuries or CVUSD chooses to suspend only in the most serious of cases.

"You have the administrators, or the whomever, the district, saying, 'Oh, you know what? As long as I don’t show high suspension rates, I can stay here for 2 to 3 years and then leapfrog over to my next job to what I really want to do. See? You look at me. Look at the change that I did,' " one of the teachers said.

Another reason for recent low suspension rates?

In late 2020, CVUSD took on the restorative justice approach, meaning instead of using punitive discipline on kids who break the rules, they use counseling guidance and mediation in response.

The district has said this approach is working, especially at the middle school level. Still, safety or, the lack of it, is top of mind for teachers.

"When the fire alarm goes off at CV High School, nobody moves. Why? Because it's constantly pulled. Then we wait. And we wait. And we wait. And then we hear it was a false alarm. One day we're going to burn up, and nobody's going to move. There's going to be a real fire. And we don't have lockdowns when there's gun scares," one of the teachers said.

Chronic issues of safety and instability have long plagued CVUSD, like its troubled history with its top teacher. In just the past decade, the district has seen a revolving door of five different superintendents.

From 2010 on to 2011, there was Dr. Ricardo Medina, who was fired by the school board.

From 2011 to 2016, Dr. Darryl Adams was in office but ended in resignation, citing health reasons during any ugly showdown with the teachers' union.

From 2016 to 2017, Edwin Gomez was named superintendent but ultimately resigned for a county job.

From 2019 to 2021, Dr. Maria Gandera took on the superintendent job but abruptly resigned before her contract was up, getting paid out nearly $300,000 after signing an agreement that she would not disparage the district, among other things. You can read the agreement here.

And from 2021 to present day, Dr. Luis Valentino heads up CVUSD.

For reference, the average tenure of a superintendent is about six years, according to a Broad Center Yale University study. In the same time frame, DSUSD and PSUSD have both seen three superintendents, with all past leaders ending in retirement.

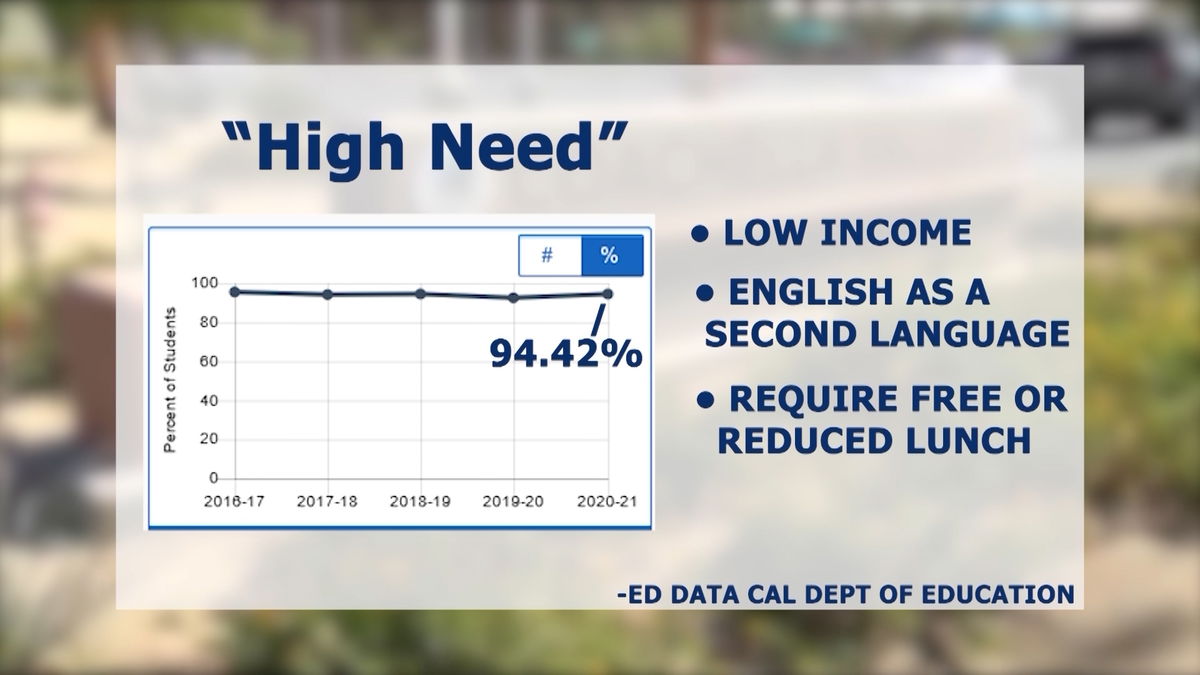

To be fair, CVUSD does face some tougher challenges. More than 90 percent of the students at CVUSD are categorized as "high need," meaning the students are classified as low-income, English as a second language speakers, or require free or reduced lunch meals.

"There's kind of instability, economically, that comes from either job loss or poverty, that has effects on your health. It has effects on your mental health. Food Insecurity is a big one as well," Lafortune said.

It's certainly a tough job to lift a district entrenched in poverty, but teachers believe the power of change will have to come from students and parents. One teacher left a plea to all students and parents.

"I need you to understand that your voice matters," one of the teachers said. "You need to demand the change from your school board, and when they don't give you that change, you need to vote them out."